In a diverse society like Malaysia, national schools play a crucial role in bringing together pupils from various backgrounds to foster national unity. The National Education Blueprint 2013-2025 acknowledges the importance of education in nation-building and unity, recognising that schools should create a shared learning experience for pupils of different social, cultural, religious and economic backgrounds. However, there is contention on whether the existence of vernacular schools undermines the goal of public schools to cultivate a common national identity.

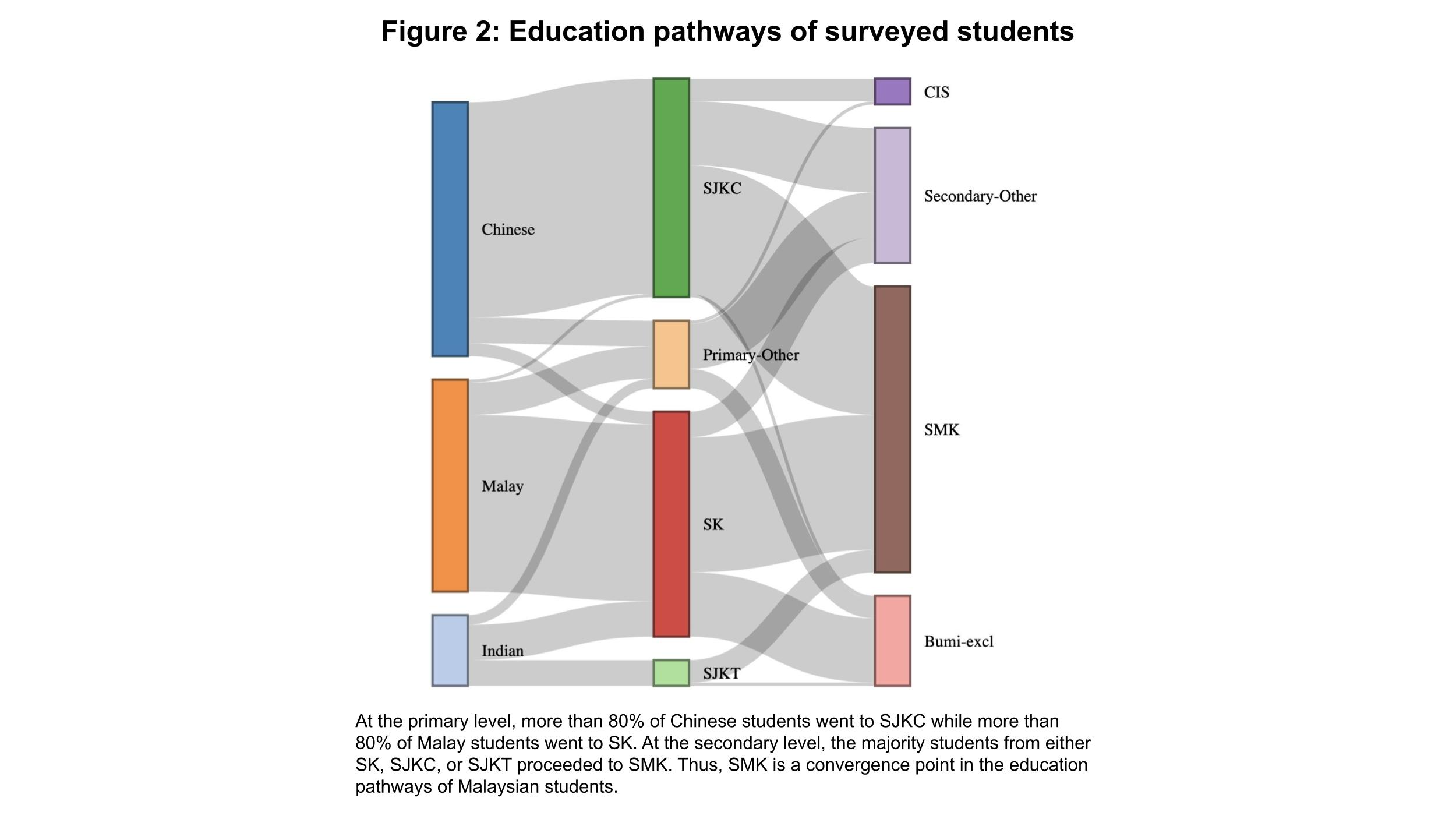

Vernacular schools are often relatively ethnically homogeneous. In the same blueprint, the Education Ministry reported that Chinese pupils made up 88% of the population in Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan Cina (SJKC), while Indian pupils made up 100% of enrolment in Sekolah Jenis Kebangsaan Tamil (SJKT). The same is true for Maktab Rendah Sains MARA (MRSM) and Sekolah Berasrama Penuh (SBP), where most of the pupil population are Bumiputera.

But do ethnically homogenous schools really lead to greater ethnic divisions?

To attempt to answer this question, I collected an ethnically representative sample of personal friendship networks of university students from both public and private universities. The goal was to explore whether the school type someone attended earlier in life affects the ethnic diversity of their friendship networks later in life. Focusing on friendships is one way to explore whether attending certain schools leads to greater or less ethnic divisions, with potential implications on how Malaysia’s public education system can be designed to promote greater national unity.

Two key findings emerged.

Firstly, respondents tend to have friends of the same ethnicity regardless of their schooling background. This is the effect of ethnic homophily, or the tendency for individuals to associate with those who are from the same ethnic group. At the university level, Malay students are more likely to associate with other Malay students, Chinese students with other Chinese students, and Indian students with other Indian students, regardless of their prior school type.

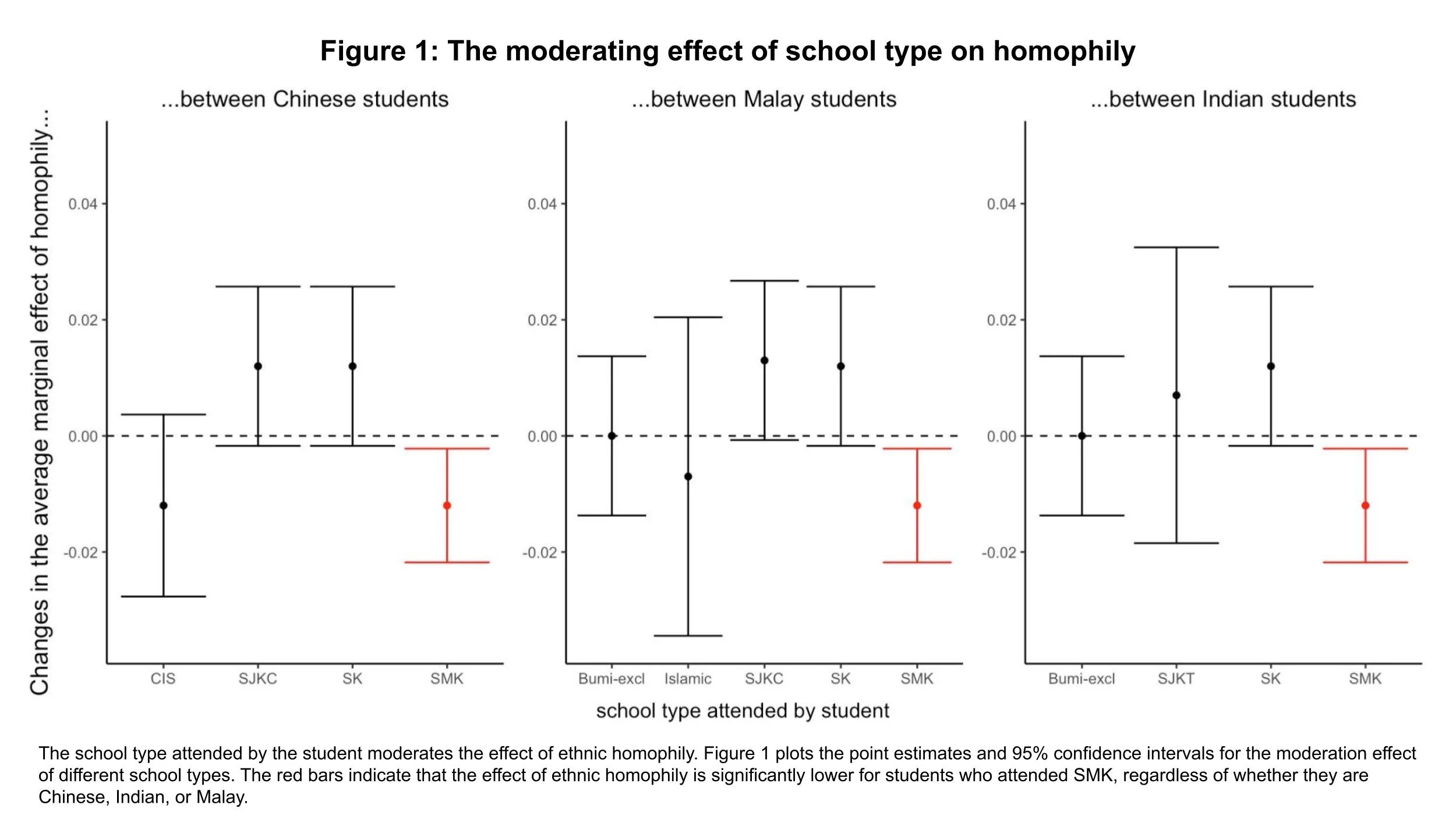

Secondly, while ethnic homophily is the driving force behind friendship formation for Malaysians of all ethnicities, the school type an individual attended earlier in life moderates the strength of the homophilic tendency. Specifically, ethnic homophily is weaker among students who attended SMK, suggesting that SMK promotes more diverse friendships. On the contrary, attending ethnically homogeneous schools – i.e. vernacular schools, MRSM, SBP or Chinese independent schools (CIS) – neither strengthens nor weakens ethnic homophily. This means that a person who attended an ethnically homogeneous school is no more likely to have friends of the same ethnicity than baseline expectations. Put simply, attending an ethnically homogenous school does not mean that friendships later in life will be homogenous.

Why is attending SMK associated with lower ethnic homophily, while attending other schools seem to have no effect? The answer most likely lies in the ethnic diversity at SMK.

SMK is a common choice for students from all ethnicities because of its affordability and accessibility. It serves the role of that national schools do in plural societies, being a key point of convergence in the lives of students. Interaction between students of different backgrounds in national schools can work to reduce prejudice and increase acceptance towards people of different ethnic backgrounds. My survey data corroborates this explanation: students education pathways diverge by ethnicity at primary school, but they converge at SMK.

What this means for Malaysia is that the key to fostering greater national unity is to create more opportunities for meaningful interethnic contact between pupils in different schools. This can be much more easily done than shutting down ethnically homogenous institutions, not least because of a recent court of appeal ruling that upheld the constitutionality of vernacular schools and the use of Mandarin and Tamil as the medium of instruction at these schools.

One way to create opportunities for meaningful interethnic contact is through initiatives like the Rancangan Integrasi Murid Untuk Perpaduan (RIMUP). The programme allows pupils from different school types to interact through a range of activities including extracurricular classes, motivation camps and sports events. Nevertheless, more needs to be done to ensure these programmes facilitate interactions between pupils that are natural instead of forced. This means a need to be more student-driven, focusing on activities that students enjoy. Additionally, to increase participation, there is also a need to increase public awareness of the programme and to communicate its value as a key initiative to foster stronger sense of unity and cohesion within Malaysian society.

As Malaysia prepares for the next education blueprint, policymakers can explore innovative approaches to enhance interethnic contact across different school types, with the goal of promoting greater unity and understanding among all Malaysians.

This article was first published in the New Straits Times, 18 February 2024