Article by

Bridget Welsh and Calvin Cheng

A version of this article was originally published on Malaysiakini

Yesterday, Sabah’s Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO) was extended until November 9 – making it over a month that the state will face serious hardship as its citizens struggle to get the virus under control. A total 889 cases of Covid-19 were reported on October 24, with a total of 9,408 cases since the start of the month. A total of 90 Sabahans have died from the novel coronavirus – a death rate of over seven times higher than the national average.

This piece continues to draw attention to the key issues in Sabah’s Covid-19 crisis, with particular attention to the challenging socio-economic conditions on the ground. Beyond the public health dimensions, Sabah’s Covid-19 crisis is much larger, exposing deep socio-economic vulnerabilities and highlighting the long-term neglect of this state. This is now an emerging humanitarian crisis. Assistance needs to go beyond healthcare to ensure that Sabahans have the resources to survive the crisis and are in positions to recover whenever the health situation is stabilised.

Rise in cases expected

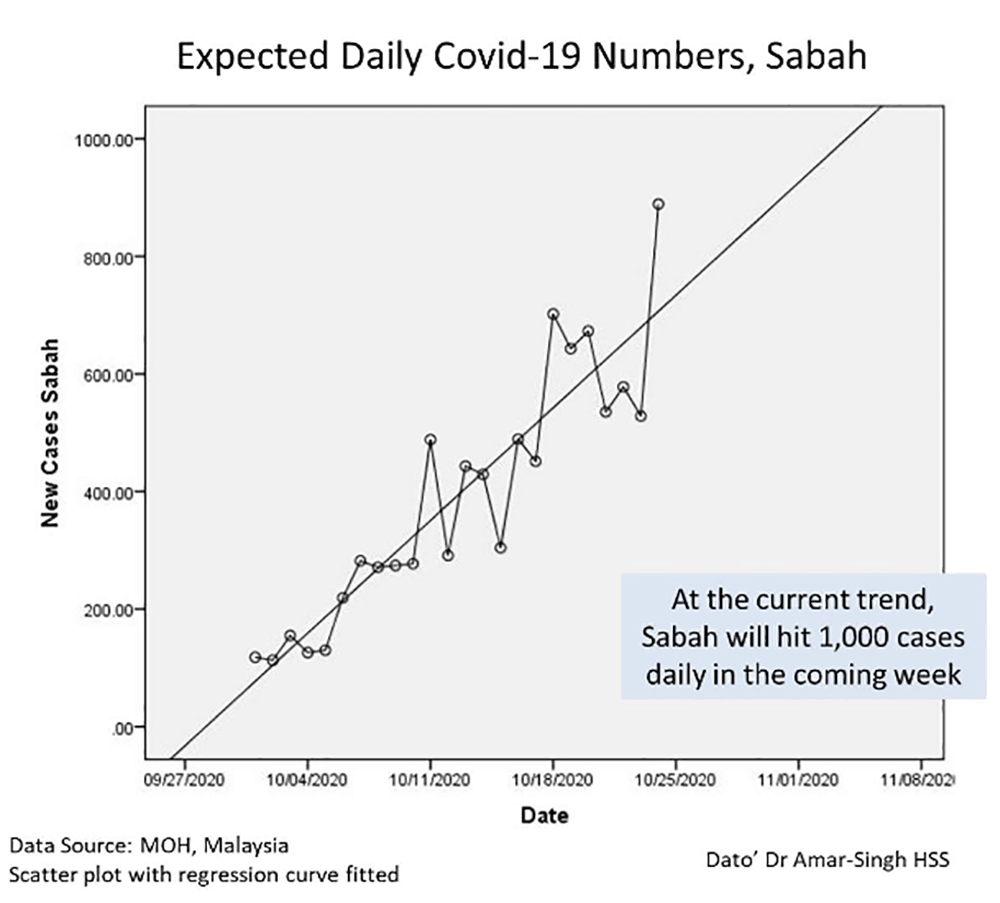

Our focus starts with a look at the health situation. By many measures, the case numbers in Sabah will only continue to increase. The trajectory, based on recent positive infections, point to the reality that infections in Sabah alone may cross the 1,000 case number mark. Deaths, too, will also likely cross a threshold of over 100 Sabahans. This means that the strain on healthcare facilities – and the accompanying fear and anxiety – will intensify.

Wide community spread

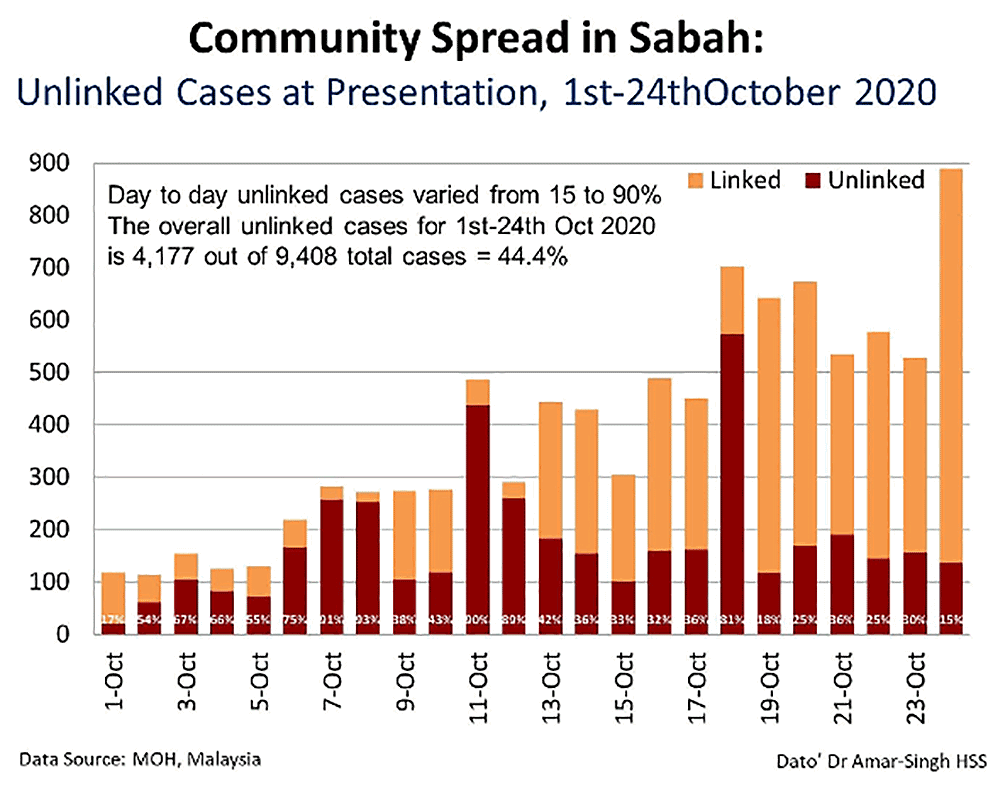

This is reinforced by persistent trends showing that nearly a third of the cases remain unlinked. The share of unlinked cases yesterday dropped due to the high cases in the Kepayan prison (allowing for clear tracing), but despite all the hard work being done, a large number of cases still cannot be traced. This month, from October 1-24, a total of 4,177 out of the 9,408 cases, or 44.4 percent, of the Sabah cases remain unlinked – almost every other person. This suggests that the virus is already widespread in the community, emphasising that the need to adopt new approaches is more pressing than ever.

To address this health crisis, four herald calls need to be urgently acted on.

More resources: A ‘surge of federal resources’ is needed. This needs to address the inadequate personnel, equipment, beds and serious backlog in testing, which is costing lives and destroying livelihoods. Current levels of funding are just not enough. A crucial part of the resources needed is stronger ties with professional experts and local civil society leaders who can offer new ideas to address the ongoing crisis. Additional personnel from West Malaysia are needed to support hospitals and contact tracing efforts.

Testing: Second, more widespread testing is needed. The Health Ministry’s refusal to follow international recommendations of ‘test, test, test’ is misguided. Affordable and mobile tests are readily available, and they should be carried out. Without proper testing, the situation will continue to worsen and will not be able to be properly controlled, given the degree of community spread.

Transparency: Third is the need for greater transparency in data. There have been conflicting reports regarding the Sabah state and federal government on bed availability and these differences have raised concerns. The Health Ministry needs to properly cooperate with local authorities, provide positivity rates weekly by state and district not in broad unusable bands, report turnaround on tests by state and show admission and severity rates.

This is the time for outreach, not retreat. Sharing (non-personal) data will allow for stronger collaboration to address the crisis in Sabah and allow us to prepare proactively for emergent health crises in other parts of Malaysia.

Frontliner support: Finally, there is a need to appreciate the toll that this crisis is placing on the brave and dedicated medical frontliners. There is a high rate of infection among medical staff, and many in the field are reaching a breaking point. As such, there needs to be greater rotation of personnel and relief as the crisis is one for a longer haul – most certainly much longer than the few weeks that was originally suggested when the crisis was being brought to public attention. This only further emphasises that more needs to be done especially at the federal level. At the very least, there needs to be more investment in people responding to the virus for the protection of the people facing the virus.

Greater local engagement

Nonetheless, as the crisis has continued, there have been overall positive developments this week. We have seen three marked shifts:

Greater state intervention: The Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) state government has stepped up, with a more honest recognition of the issues and greater engagement. Ministers have been open about the strain on health facilities and need to move toward self-isolation as there is not enough space in existing facilities. Improved communication has been accompanied by a better appreciation of the seriousness of the situation on the ground.

There is still more that can be done by the state leadership, with an appointment of a health minister or state task force, but credit should be given to the greater interventions by the state government.

Broadening civil society engagement: At the same time, the engagement of civil society organisations has broadened. Support for healthcare professionals has been heartening and extensive. It is the less publicised efforts, however, that are especially impactful, as thousands are being fed by the kindness of strangers. As will be noted below, the socio-economic effects of the crisis extend far beyond the health issues, but also reinforces pressures on the health system.

Calling out uneven and gaps in federal support: We have seen at the federal level broader engagement by the army and the police, including the opening up of an army hospital in Tawau and outreach and awareness campaigns by the police about the difficult circumstances on the ground.

These organisations can play a supporting role in the mobilisation effort but given the reality of undocumented persons and deep distrust of the federal government, cannot play a leading role. There needs to be a stronger collaboration, with civil society leadership and participation at the fore.

While the Health Ministry continues to report support to Sabah – and this support is real and extremely important – there is a growing gap between what is needed and being provided. These concerns are being raised publicly, notably on social media as public accountability is playing an important role in the crisis in Sabah.

Perceived gaps, however, are fueling dissatisfaction among the public. As tensions rise and conditions worsen, the need for improving cooperation and greater respect for and appreciation of the local conditions are needed more than ever. A key step moving forward remains greater decentralisation of the effort, as the crisis has moved beyond what officials in Kuala Lumpur are fully capable of addressing without greater outreach and local participation.

Sabah’s economic challenges continue to mount

Of course, Sabah’s Covid-19 situation transcends health. A crucial part of this is recognising the truly desperate economic circumstances on the ground, especially in certain areas in Sabah. Many of these are legacy issues arising from failings in policy in the past, with the crisis bringing deep vulnerabilities to the surface.

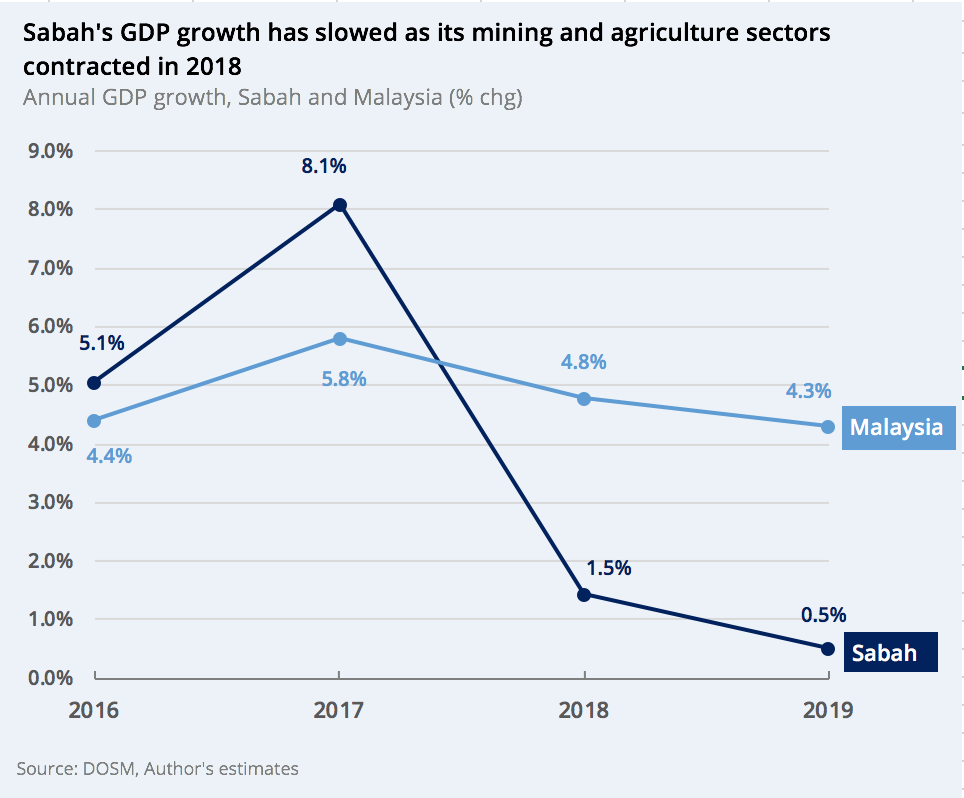

Even before 2020, Sabah’s economy had been in a tight spot. The state’s relatively high exposure to commodity-related economic activity (roughly half of the Sabah economy in 2019 was derived from commodity agriculture and mining), along with a sizable tourism sector, means that a large share of Sabah’s economy is subject to the whims of the global economy.

Over the past two years, global trade tensions and lower world commodity prices have dampened Sabah’s agricultural and mining sectors, bringing Sabah’s GDP growth down from 8.1 percent in 2017 to a just 0.5 percent in 2019. At the same time, longer-term challenges like elevated levels of unemployment, poverty and issues with access to basic infrastructure in certain districts remain urgent.

Sabah’s Covid-19 crisis reinforces these negative existing trends. Initial reports suggest that the large global and domestic demand shocks brought upon by the pandemic have already decimated economic activity in the large swathes of the Sabah economy. Hotels are being sold. Stores and businesses shut down. Despite past half-hearted attempts at stimulus by both the federal and Sabah state governments (which had implementation issues), economic growth in the state will almost certainly be deeply negative in 2020.

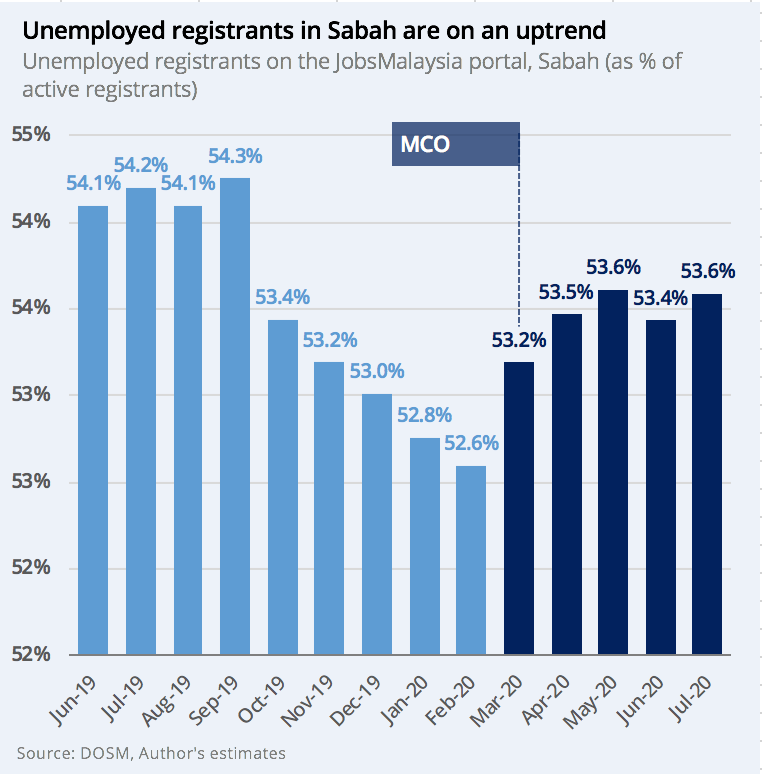

Yet, while these macroeconomic trends are concerning, it is the negative effects on workers and households that are even more frightening. Everyday Sabahans are struggling. While real-time state-level employment data is lacking, recent JobsMalaysia data suggests that workers in Sabah have not fared well. Since the first Movement Control Order was enacted in March 2020, the share of unemployed active registrants on the JobsMalaysia portal in Sabah has risen steadily over the ensuing months. At the same time, job opportunities have become scarcer, with job listings in Sabah declining by about 70 percent in 2020 compared to the same period last year.

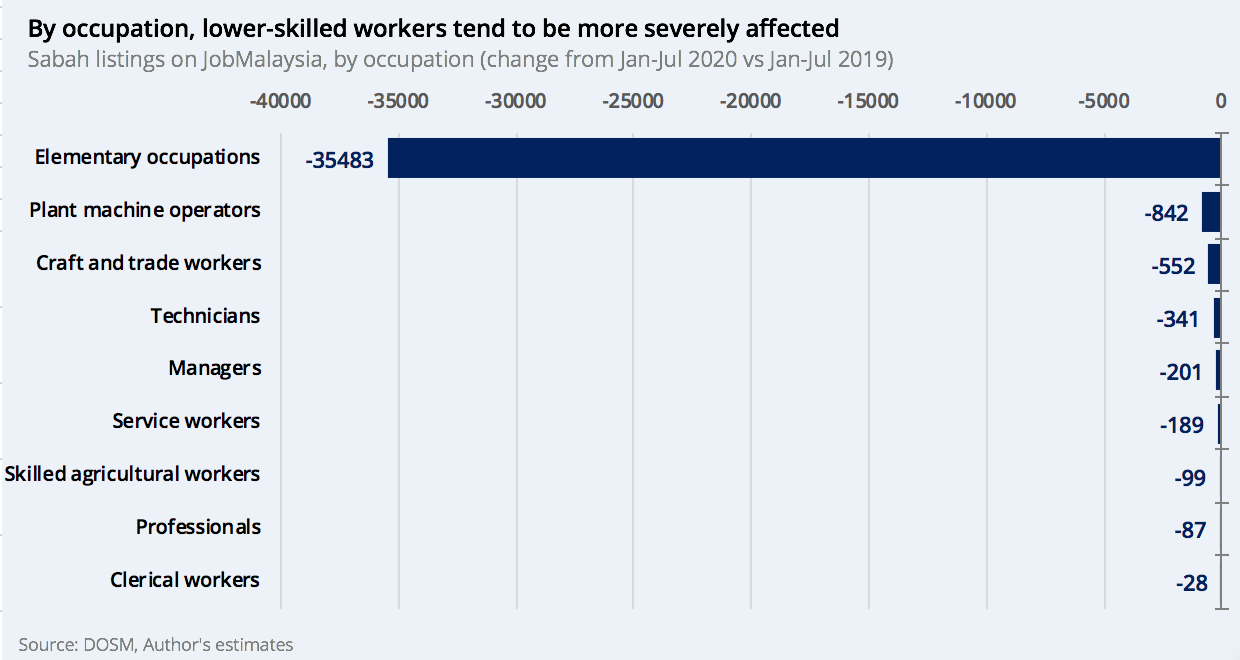

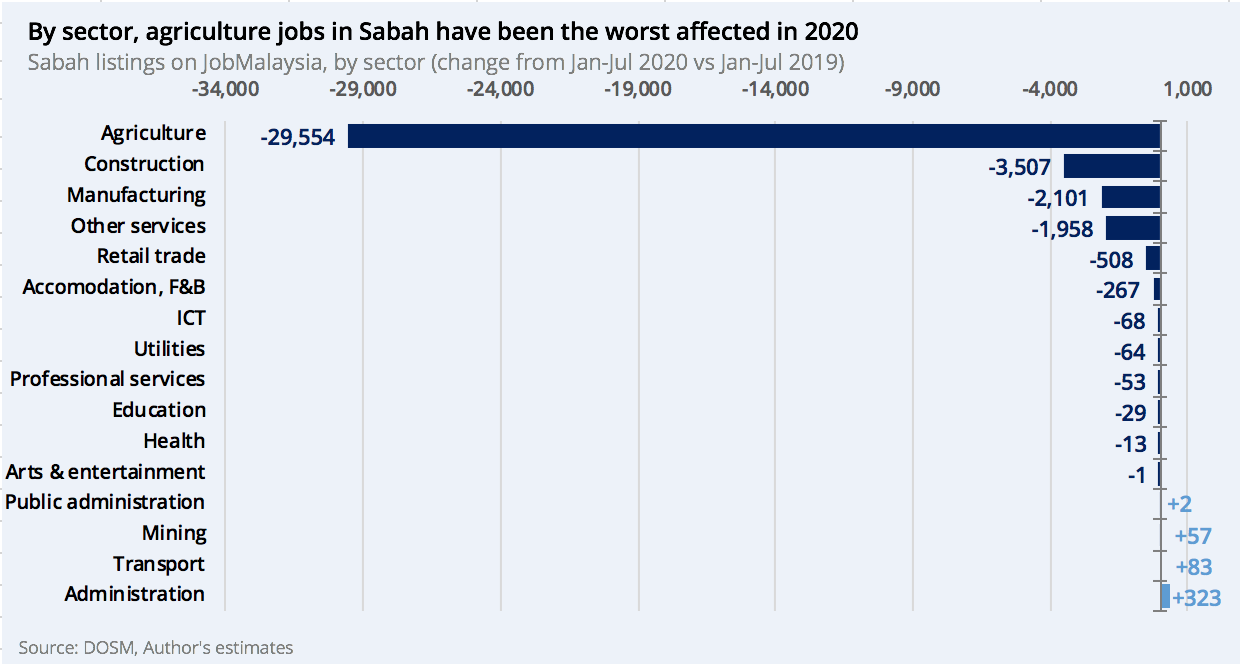

Looking at the types of jobs that are affected, the data suggests that in Sabah, just like in the rest of the country, the negative impacts of the pandemic have been highly uneven. Elementary and/or lower-skilled occupations have been the most heavily impacted by far, with Sabah’s listings of job openings for elementary occupations, machine operators and trade workers declining by more than 35,000 jobs in 2020 compared with the same period last year. By industry, many of these ‘lost’ jobs are in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector – which employs more workers than any other sector in Sabah. In 2019, the agriculture-related sectors accounted for more than a quarter of the total employment in the state.

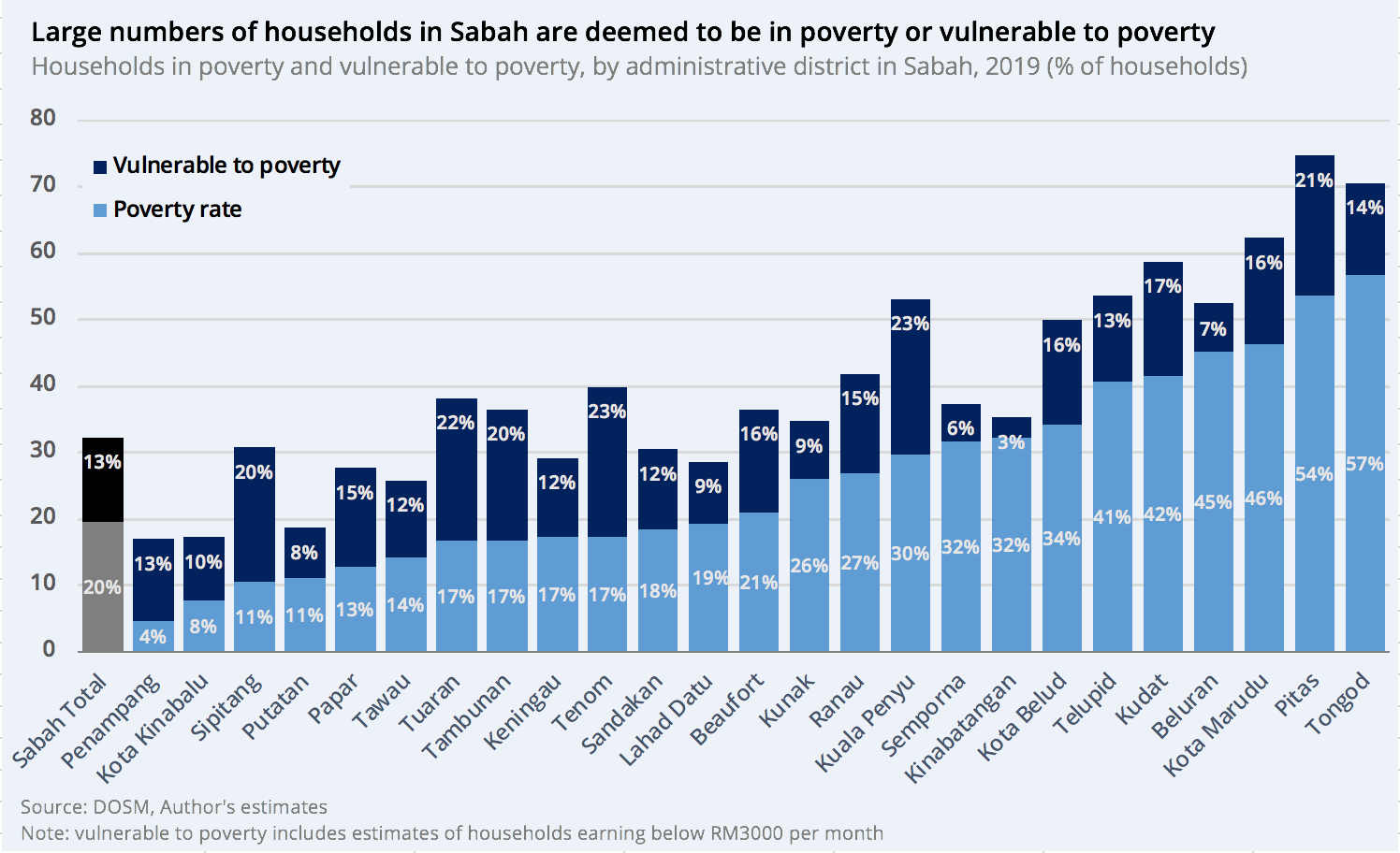

More recently, with the persistent serious health situation, the effects of Sabah’s Covid-19 crisis has extended from the economy into society. It is an unfortunate fact that Sabah has the highest household poverty rate in the country, 19.5 percent of households – roughly estimated to be about 450,300 persons. Based on household survey data, we look at the share of those with incomes under RM3,000 per month as well as those below the poverty line income of RM2,208 per month, pointing to those who are most vulnerable in a time of economic contraction.

Conservatively the proportion of vulnerable households in Sabah is about 33 percent, roughly estimated at about 743,000 people. In other words, this could be one out of every three Sabahans. Certainly, a more accurate figure of those vulnerable is likely even higher – official statistics often leave out the estimated one million undocumented persons in the state. This economic precarity extends throughout Sabah, but eight districts, detailed below, have more than half of their populations facing dire circumstances with two of these – Pitas and Tongod – having over 70 percent affected.

In any case, these disturbing statistics suggest that there is a humanitarian crisis fast emerging from the economic contraction tied to the pandemic. This is being corroborated by field reports of serious hunger and deprivation in parts of the state. Many Sabahans are starving and more will starve without financial support.

The complexities on the ground have made the distribution of food aid challenging, and there has been inadequate cooperation and support to strengthen local civil society networks to give them access to communities who distrust officials, especially federal officials. No matter what lenses are used to levy blame for the crisis, the buck stops with the federal government which has allowed this vulnerability and suffering to continue, and for weeks refused to acknowledge that a crisis was unfolding. Keep in mind that hunger feeds desperation and will contribute to a worsening the health situation. Some infected persons may not have the strength to even get tested, as the risks of deaths coming from other dimensions of the crisis loom over the horizon. More holistic and inclusive interventions are needed.

Humanitarian financial response

These sorts of crisis intervention cannot be effectively carried out under an ‘emergency rule’ situation being articulated by Muhyiddin Yassin’s government, a situation that takes away rights and the alternative voices and potentially disempowers civil society that is crucial for outreach as a humanitarian crisis unfolds.

What is needed instead are special measures that harnessed emergency aid and assistance, that work and respect people and recognise the unique and challenging circumstances ahead – an inclusive approach that appreciates urgency, does not replicate the delays to date and builds trust on the ground

Beyond the needed greater health resources, an urgent package of financial assistance earmarked for Sabah is needed – one that is accountable and transparent to prevent graft and corruption (another reason for accountability and oversight that cannot be assured under an ‘emergency rule’).

There needs to be a discussion on these issues in Parliament and in the state assembly. This special relief for Sabah should be distributed as soon as possible. Given Sabah’s contributions to oil and gas revenue, one alternative is a special allocation of the royalty revenue or other shares of funds from oil and gas income in the state. Civil society groups will not be able to sustain support for the growing humanitarian and persistently grave crisis.

Delays in responding allowed the Sabah’s Covid-19 crisis to deepen. Timely, decisive intervention can help to safeguard the welfare of Sabahans, and stop the socio-economic damage from Covid-19 from further evolving into a humanitarian crisis.