Failure to produce critical thinkers could scuttle Malaysia’s high-income ambition

Malaysia is now at a crossroads on the education front. The nation is striving for high-income status, which requires producing enough skilled workers for advancement, yet there are deep-rooted challenges within the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) education system that have impeded progress for decades.

To meet these challenges, the government unveiled two measures related to STEM in Budget 2024: the establishment of an Inter-Ministerial STEM Committee and a RM100 million allocation for new equipment and upgrading of computer labs.

While these measures are a positive start, they fall short of addressing the key challenges within the education system itself.

To start, there was no mention of measures to address competency issues among STEM educators. One of the core obstacles has always been that STEM teachers themselves generally lack the requisite qualifications and/or knowledge to teach STEM.

Woeful teaching quality

An Academy of Sciences Malaysia (ASM) report indicates that nearly half of the total science

teachers in Malaysia do not even have a bachelor’s degree. This is exacerbated by limited opportunities for teachers to undergo professional development coupled with inadequate training.

For example, some teachers stressed the absence of initiatives from department heads to organise in-house training and provide comprehensive teaching guidelines. This is despite research showing that teaching quality has an outsized influence on pupil achievements and interest in STEM-related fields.

The structure in Malaysia also tends to be teacher-centred and textbook-focused, with a strong emphasis on rote learning. This points to a deficiency in prioritising high-order thinking skills and inquiry-based education, fostering an environment where pupils are passive recipients of knowledge, rather than engaging in critical thinking. This pedagogy has resulted in pupils who lack the capabilities of innovative and creative thinking necessary for success in STEM fields.

Another challenge in STEM education is inadequate infrastructure, including poor lab maintenance and unstable internet coverage, hindering practical teaching. This was particularly prevalent during the peak of the pandemic, which disproportionately affected rural schools.

Insufficient budget, for instance, is a key factor that contributes to the infrastructural gaps, hindering opportunities for pupils to engage in hands-on activities. The lack of support to instil enthusiasm in technical subjects resulted in pupils losing motivation on top of prejudices that STEM subjects are “too challenging”.

True enough, these shortfalls in teachers’ competency have had a discernible impact on academic performances.

Laggards on all measures

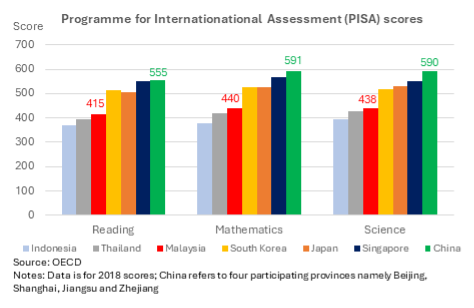

Global indicators of mastery in STEM-related subjects signal worrying conditions for Malaysia’s educational achievements relative to its regional peers. Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) results suggest that the share of Malaysian students who attained advanced level scores declined from an already low 5% in 1999 to 3% in 2019.

In contrast, Singapore jumped from 29% to 48% over the same period – 16 times over Malaysia. Likewise, Malaysian students also scored poorly in all subjects tested under the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) – reading, science and mathematics. In fact, we are substantially lower than regional benchmarks – South Korea, Japan, Singapore and China.

Recent statistics indicate that the participation rate of upper secondary pupils in STEM fell from 45.2% in 2017 to 40.94% in 2022. This makes it harder to achieve the 60:40 target of the ratio of science pupils against arts, showing the shortcomings in achieving the objectives in the Education Blueprint (2013-2025).

Almost all key performance indicators remain as primary challenges, including uplifting teaching standards, competency of teaching staff and implementation of ICT slated for completion by 2020.

These figures raise alarm as STEM plays a pivotal role in shaping Malaysia’s developmental trajectory. There is a large body of evidence linking human capital to long-term growth and a knowledge-based economy. However, research shows that this is subject to the type of education.

Innovation-centric disciplines like STEM would be a better measure of investment returns to growth as it stimulates innovation and productivity. For instance, evidence in countries, such as Azerbaijan, shows that a 28% increase in STEM jobs is expected to bring about a rise in GDP per capita by about US$1,102 (RM5,160).

The skillsets provided by STEM education can better equip Malaysians for the evolving demands of industry. As highlighted in the World Bank-TalentCorp survey, employers are reluctant to hire Malaysian graduates lacking in essential skills. These include creative and critical thinking, and problem-solving proficiency.

Moreover, since Covid-19, skills-related underemployment has risen as graduates’ skills often do not align with current industrial needs. So, STEM’s interdisciplinary curriculum stands out by not only imparting industry-ready skills but also by addressing real-world challenges in the areas of environment, care, artificial intelligence, health and cybersecurity.

Focus on educators

A World Economic Forum report shows that by 2025, around 50% of the in-demand skills would revolve around analytics, creativity, problem-solving, and ideation while 20% requires technological and programming skills.

To this end, it is imperative to address the longstanding issues of teaching standards to ensure meaningful progress on STEM outcomes.

First, hiring standards for STEM teachers must be improved. If Malaysia aims to have a higher participation rate in the stream, it should be more stringent about hiring, including requiring STEM educators to have at least a relevant bachelor’s degree or equivalent.

Such effort can be based on a multifaceted partnership model involving the Education Ministry, private sector and educational institutions. For instance, recent efforts saw a collaboration between Yayasan Petronas, the Education Ministry, Teach for Malaysia and Petrosains to implement Program Duta Guru nationwide. Strengthening cooperation of this nature could address issues like the digital divide and upgrading facilities, building on the momentum and positive response from educators.

Second, more opportunities should be given to educators to pursue proper professional development. One way is through short-term workshops, which have proven to improve teaching delivery. Especially for pre-service teachers, the training should not only comprise the understanding of theoretical concepts, but also current pedagogies that are student-centric. This emphasis mirrors Singapore’s model, which prioritises rigorous pre-service teacher education, contributing to its high international STEM ranking.

Malaysia could also replicate South Korea’s three-stage training of introductory, basic and intensive training. Pre-service educators could benefit from this approach as it focuses on best practices for STEM school and after-school curriculum. Teachers are also trained to manage hybrid arrangements and to develop their own learning materials. These would ensure only quality teachers are absorbed into the system.

It is time for policymakers to step up the game to ensure STEM education achieves its objectives despite passing a decade-long timeline. While STEM may not offer a universal solution to all developmental challenges, its outcomes could have a huge impact on the labour force and current industrial needs.