The utilisation of propaganda often has been hand-in-hand with politics since time immemorial. But with new tools – such as social media platforms, big data analytics and micro-targeted advertising – the scale, scope and precision of propaganda campaigns have increased exponentially.

In the not too distant past, rolling tanks, men with guns in their hands and bloodshed would signal the impending demise of a country’s democracy. These days, tanks have been replaced with digital propaganda campaigns – men are no longer armed with guns, but rather a combination of real, fake and “cyborg” social media accounts, and blood on the streets have been replaced with bytes of disinformation.

Subtler in nature, especially when contrasted against the coup d’etat – the traditional means of upending democracies – the consequences of digital propaganda on democracy are equally destructive. However, due to how it subtly erodes rather than outrightly upends democracies, these digital campaigns go unnoticed to most – including democracy’s traditional defenders.

Worrying is how quickly this strategy is catching on. In 2019, organised social media manipulation had taken place in 70 countries – a 150 percent increase from 2017 – according to the Oxford Computational Propaganda Research Project. As it stands, those responsible can come from three broad categories: political parties wanting to massage public opinion; foreign governments attempting to meddle in the democratic affairs of another state; and private contractors for hire.

To obfuscate their activities, cybertroopers – defined as actors acting on behalf of the government or political parties to manipulate public opinion online – use a combination of human-operated accounts, automated-bot accounts and “cyborgs” – an account that is both human-operated and automated at different times.

Further, these cybertroopers are also evolving with the times. In the past, the accounts deployed to spread propaganda were rudimentary and could be easily detected through their predominantly political content and the lack of a convincing profile picture. Today, cybertroopers make use of fake profile photos and are interspersing propaganda with organic content – giving these accounts a thicker veneer of authenticity. A consequence of this is that the ability to discern who is behind a particular account, by researchers and more so by the general public, is increasingly complicated.

Contrary to mainstream opinion, when it comes to content, these propagandists do not solely produce outrightly false content to disinform and misinform. Rather, the propagandists also seek to pollute the information environment with half-truths that seek to appeal to the baser instincts of the electorate. This is to sow confusion, widen the division between ideologies and harden the distrust between political oppositions. Besides this, cybertroopers can also deploy an army of bots to spam content with the intention of harassing individuals and to drown out and divert attention away from dissent and criticism.

In the not too distant future, these strategies could even incorporate “deepfake” technology and audio-alteration softwares to create fake audio-videos of politicians, civil society leaders, or people of interest to say literally anything at all. Bots, rather than operating on keyword-triggered scripts to respond with preset messages, can be trained through natural language processing software to respond with syntactically and contextually-accurate replies.

Taken together, the reality of today and the risk of tomorrow come at the expense of suppressed democratic participation, the zeitgeist of the day being hijacked, and the high-quality information environment that underpin healthy democracies being polluted. With that, the capability of society at large to discuss, debate and deliberate on pressing issues of concern is undermined. Of concern here is that even if individuals want to contribute to the “marketplace of ideas” through discourse, they can never be sure whether on the opposite end of their screens are genuine individuals, or an account belonging to a propagandist.

Complicating detection efforts is how with social media allowing anyone to create fictional personas, coupled with off-the-shelf Virtual Private Network (VPN) applications to mask IP addresses – only the most dedicated, technically-trained and well-funded will be able to identify these propagandists. In this sense, propagandists are simultaneously everywhere and nowhere. More nefariously, some could even claim that it is merely citizens exercising their basic freedom of expression, and not a coordinated propaganda campaign utilising cutting-edge technologies to exploit cognitive biases.

Making matters worse are countries with low public trust in the media. When coupled with a hyper-partisan political environment and coordinated propaganda campaigns to mislead, it becomes near impossible to locate common ground and agreed facts to centre discourse upon, and for compromise and ways forward to be worked out. Besides, even if the media sought to retain their traditional role as the fourth estate – the guardrail of democracy – they would have to do so at a time with decreasing revenue and a disrupted media environment where speed is prioritised over precision.

Given this, how should the defenders of democracy “fight back” and how should governments respond when the enemy cannot be seen? Against this backdrop, the silver bullet remains elusive and it will be difficult to halt the erosion of democracy. That being said, as a start there are obvious things that can and must be done.

First, governments need to invest in capacity building to ensure that it has sufficient infrastructure and personnel to identify cybertroopers. Without the capability to identify these actors, and to an extension, the nefarious narratives they are introducing to the discourse, counter messaging efforts would stand little chance.

A step further for governments would be to determine the appropriate means for accountability. If it is punitive legislations, then two issues need to be resolved. The first concerns achieving legal certainty – a key tenet of the rule of law. This would prove to be easier said than done due to the inherent difficulty in distinguishing between cybertroopers and ordinary citizens who support the cause. Further, owing to the attendant complexity in identifying a definition for the crime – one that is specific enough to not risk casting a chilling effect on free speech, yet sufficiently broad to penalise those responsible – punitive legislations would require the most deliberate legislating.

The second is that cybertroopers – especially those involved in influence operations – could operate outside of the country’s jurisdiction, raising questions pertaining to the punitive legislation’s extraterritorial applicability and whether mutual legal assistance would be granted. Here, there is also a risk for authoritarian states to “learn” from the example of what is being done in democratic countries, and to use these to justify their own versions of anti-foreign influence laws. As there is a fine line between cybertroopers influencing a democracy, and genuine dissidents of a regime, this line can be easily and conveniently obfuscated to serve as a tool to silence dissent.

Second, politicians need to commit to higher levels of transparency when it comes to their digital media engagement. It is not wrong for those in politics, through internal capacity or by engaging private contractors to spread their politics, policies and position, but the people should know when they are consuming content originating from a political party or politician. Here, offline norms of politics, such as transparency in political stances concerning key issues to the electorate, should be replicated in the cyber realm.

Third, more must be demanded of social media companies. Efforts have been made towards ensuring political advertisements are flagged as such, but users also should have the right to know whether an account belongs to an individual or is part of a cybertrooper’s arsenal of accounts. Similarly, social media companies should make known whether content is being amplified by cybertroopers and how its algorithms are interacting with the content the users are seeing.

Additionally, social media companies should figure out its values and the kinds of behaviour that it deems to be problematic. If actions, such as spreading propaganda and micro-targeting of voters based on browsing patterns are deemed to be contrary to those values, then companies need to anchor their responses in that value, and take the appropriate actions including deplatforming. While some might question the value of deplatforming as admittedly there is nothing stopping cybertroopers from creating new accounts, its effect on increasing the financial and time costs for these cybertroopers to amass new followers should not be discounted. A similar strategy had worked well for countering radicalisation content on social media and the same could work in terms of digital propaganda as well.

Fourth, and perhaps most important here is for society and the traditional defenders of democracy to step up their game. The electorate need to be cognisant that these cybertrooper strategies are only as effective as the existing pressure points in the societies within which they operate. For a while now, there has been a growing sentiment that democracies have not been able to produce the proverbial “bread and butter” for the people, and this sentiment could only be exacerbated once the forces of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, climate crisis and economic inequality fully take holds and its effects set in.

In fact, to some today, it seems to be the case that what matters most is whether the government – regardless of whether it is a liberal democracy, semi-democracy, or even authoritarian – is able to provide the public goods for its people. The cases of China, Singapore and maybe even Rwanda in the future, is testament to benevolent authoritarianism being a legitimate means of governance despite what those holding onto liberal values might feel about them.

That said, democracy and democratisation can no longer be honestly said to be historically determined, or an inevitability as nations and its people grows richer. The modernisation theory – that as a country’s middle class increases in size so will the demand for democracy – has never been further from the truth as it is now.

Considering this, what needs to happen instead is for the people living in democracies to have genuine, meaningful conversations about the direction their politics is heading towards, and the implications of the choice of platforms for discourse today having shifted from the commons owned by the public to the privately-owned social media.

In the same vein, there needs to be a reconsideration of how political institutions, regulations and norms that were formed in the analogue age should adapt and evolve for the digital age. Ethical questions about the usage of personal data and big data analytics to inform micro-targeted political messages, algorithms skewed towards the extremities of viewpoints to hold attention spans, among many others, need to be debated and deliberated.

As democracies stand at this inflection point, the whole of society needs to resist from the temptation of retreating towards illiberal policies and legislations to ostensibly protect liberal democratic institutions. While this could pay dividends in the short term, the democratic price to pay in the long term will be unsustainable. Here, it bears worth remembering the old adage, “the cure for the ills of democracy is more democracy”.

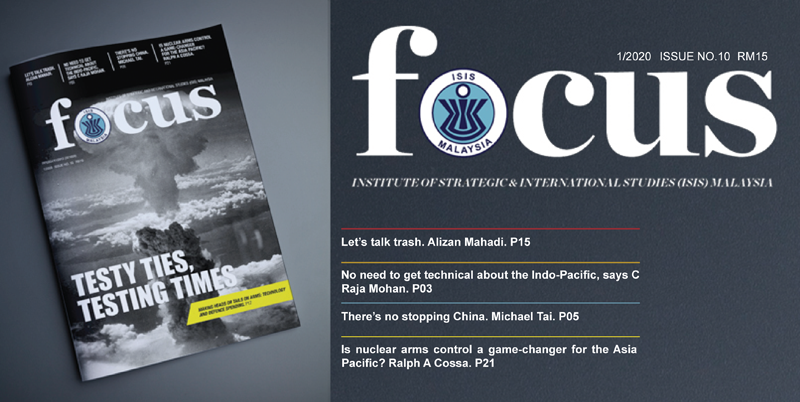

This article first appeared in the ISIS Focus 1/2020 No. 10