OUR WAY: We can break away from the Western model of growth

World leaders will once again congregate in New York from this Sept 25 to 27 this year. They will adopt the Post-2015 Development Agenda, aiming to change the world in 17 steps with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030.

In Seoul last month, the Korean Association for International Development and Cooperation (KAIDEC) had convened a meeting of development experts to discuss Asian perspectives on the new set of goals, targets and indicators that will re-place the Millennium Development Goals. At a glance, it makes little sense to advance the proposition that there is such a thing as an Asian identity. Geographically, yes, Asia can be considered one single entity comprising contiguous territories. But, we are used to a truism that countries in the region are so diverse in their histories, resource endowments, cultures, living standards, and political systems.

This explains why it is difficult to form common perspectives on economic development model for the peoples of Asia. Some leaders and intellectuals had once proposed that Asia’s industrialising nations share some values that led them to economic success. However, this idea eventually waned with the Asian financial crisis in 1997.

Sceptics may even say that Asia’s development path should be avoided rather than emulated. With rapid economic growth within just a few decades, Asian megacities and their 4.3 billion people have experienced intensive environmental disruption. Land use change has caused biodiversity loss and compromised environmental life-support systems with a knock-on effect on human livelihoods and wellbeing.

Such argument is probably true at the macro level. To find some wisdom about sustainable development practices in Asia, we have to look closer by observing how contemporary Asian communities respond to environmental changes.

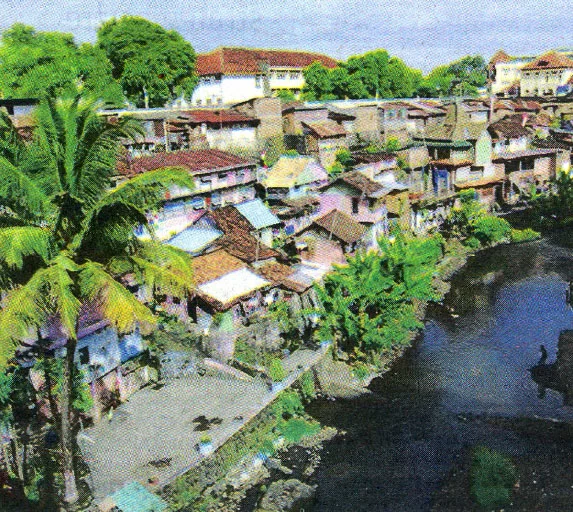

In Jogjakarta, Indonesia, a local community group called Pemerti Kali Code -meaning the preservers of the Code river -has championed initiatives to promote sustainable development. In this urban setting of about 14,000 -riverbank people, Pemerti Kali Code has led alternative livelihood programmes, river-walk tourism, environmental rehabilitation and disaster mitigation to revitalise the living conditions of the urban poor.

As in other places in Asia, Kali Code especially benefited from the presence of a visionary leader in the person of Totok Pratopo. This former teacher has managed to unite the diverse groups behind a common vision of sustainability. His leadership has mobilised local activism by navigating within and between the social spaces in order to build trust and forge links between multiple actors and institutions.

Khiriwong has made a name for itself among tourists and scholars beyond the Nakhon Si Thammarat province in Thailand, where it is located. The village is known for the community’s ability to strike a harmonious relationship with nature. Since the first settlement was established there two centuries ago, the community has learned to adapt to environmental risks on the mountain terrain.

One strategy employed is -a fruit cultivation system that they call the Suan Som Rom. This fruit farming method mimics nature by ensuring the rooting and canopy arrangements of the fruit trees resemble the natural forest. The end-result is an “integrated garden” in which the cultivated fruit trees

The riverside community of Kali Code in Jogjakarta in Indonesia. Its residents have revitalised its urban living conditions are grown alongside indigenous forest trees. By mixing the trees, the community had adopted an ecologically sound method of stabilising loose granitic soil on the steep slopes, which is less likely to cave in after heavy rainfall.

Also, in many parts of Asia, a reverence for the spirits of the natural world still governs the behaviour of its peoples in daily interactions with the environment. Biwa-ko, the largest lake in Japan, has a distinctive Shinto temple gate in its waters as a reminder that this is a sacred place that should be protected by all. In the scenic isles of Batanes in the northernmost tip of the Philippines, a shaman performs the vanua ritual to appease the spirits so that fishermen are safe at sea and enjoy a good catch for the season. In Peninsular Malaysia’s Tasik Chini, the indigenous Jakun community uses oral traditions to remember their ancestors and pay respects to powerful spirits to sustain the human-nature balance.

The examples above are extracted from a book entitled Living Landscapes, Connected Communities: Culture, Environment and Change Across Asia. Its findings point to our common Asian heritage of spirituality, community solidarity and moral leadership. Despite belonging to different national contexts, there is unity in the rich variety of Asian cultures. The more than 300page book is a culmination of a five-year study by hundreds of fellows of the Asian Public Intellectuals Programme. Together, these “cultural commuters” have taken the initial step to liberate ourselves from cultural myopia, by understanding the interconnectedness of Asian legacies and values. More needs to be done surely to piece together the jigsaw of alternative development and ecological change in Asia.

We arguably have a case to promote Asian perspectives on sustainable development and SDGs based on ways of life that are closely linked to nature. By extension, we are also presented with an opportunity to re-examine the global dominant model of development and quantitative growth, and perhaps, break away from it for good

Article by Dr Hezri Adnan which appeared in New Straits Times, 8 September 2015.