Jaideep Singh was quoted in The Edge Malaysia, 18 August 2025

By Esther Lee

THE 19% tariff rate agreed to by Malaysia on goods exported to the US has unsurprisingly raised this question: Did Malaysia give up too much for the rate?

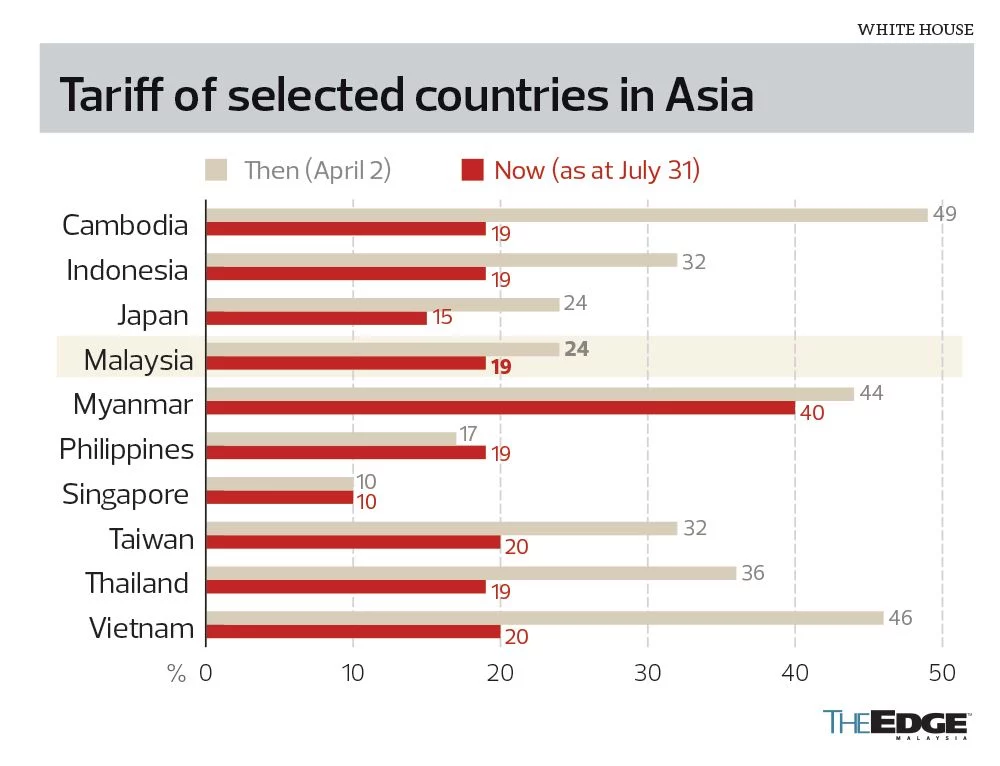

Those who look at the glass as half full would say that the rate is a relief, considering that the earlier tariff rate threatened by the US was 25%. But some believe Malaysia could have got a better deal.

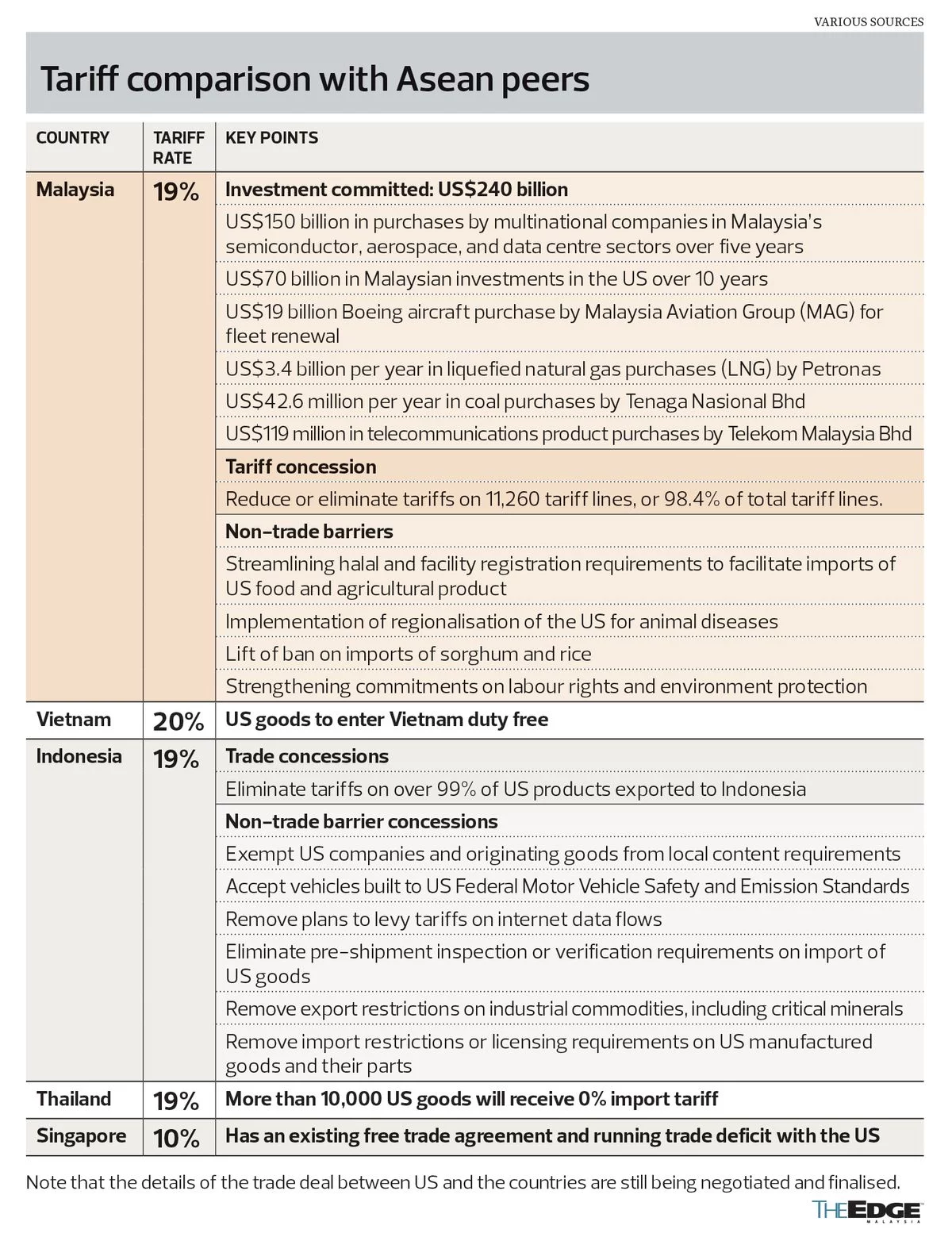

Apart from the US$240 billion (RM1.01 trillion) purchases and investments committed to the US, some of which include multi-year agreements and deals made earlier, Malaysia — like its Asean neighbours — has agreed to cut tariffs on almost all US imported goods. Malaysia has also abolished the requirement for US social media platforms and Cloud Service Providers to contribute 6% of their total income in Malaysia to the Universal Service Provision (USP) Fund.

However, before the market could digest what all this meant for Malaysia, US President Donald Trump remarked late last week that the country will impose a tariff “of about 100%” on semiconductor imports, except those from companies that are manufacturing in the US or have committed to do so.

Indeed, the market was waiting for Trump’s move on semiconductor and pharmaceutical exports to the US, which had been exempted from reciprocal tariffs. Both items were under investigation by the US Department of Commerce under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act 1962. Economists contacted by The Edge say it is hard to say what the impact of the US’ measures would be on Malaysia at this juncture, given the lack of details of the implementation, effective date and how extensive the exemptions for firms that invest in the US will be.

Economists contacted by The Edge say it is hard to say what the impact of the US’ measures would be on Malaysia at this juncture, given the lack of details of the implementation, effective date and how extensive the exemptions for firms that invest in the US will be.

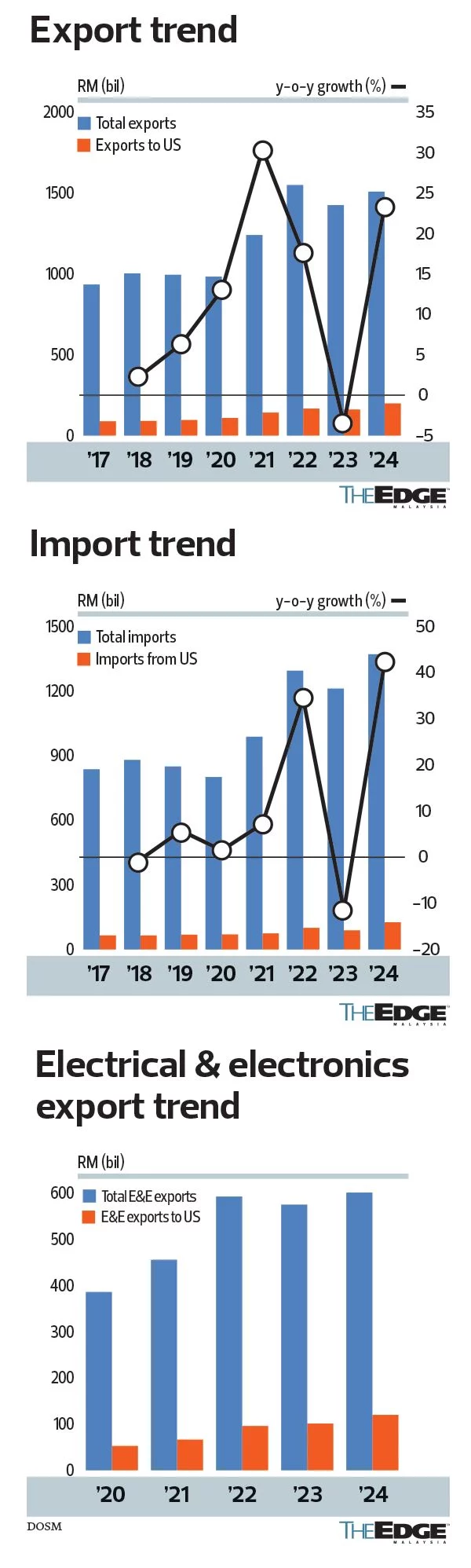

Currently, about 68% of Malaysian exports are impacted by the US tariffs while 32%, mainly electrical and electronics (E&E) related products, are exempted, notes UOB Global Economics and Markets Research senior economist Julia Goh. This implies that the focus will now fall on the remaining 32% of exports currently exempted from tariffs.

In a written reply to questions from The Edge, Minster of Investment, Trade and Industry (Miti) Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Abdul Aziz says while a significant portion of Malaysia’s exports to the US comprises E&E products, they consist of mostly inputs or intermediate goods for further manufacturing lines in the US and not consumables.

“Sixty-five per cent of our exports of E&E to the US are from US multinational corporations (MNCs) operating in Malaysia,” he notes, reiterating that Malaysia will continue its engagements with the US on the semiconductor tariff.

The minister stresses that most of Malaysia’s E&E production is not meant to compete with the US semiconductor industry but complement it and the supply chain, with the successful execution of the US semiconductor industry supported by a global network of partners like Malaysia which plays a strategic role in assembly, testing and packaging.

Michelle Chia, head of research of CIMB Treasury and Market Research tells The Edge that the fact that 65% of Malaysia’s chip exports to the US are produced by American firms in Malaysia should provide some degree of protection — in the form of exemptions — for chip trade flow to the country.

“In the short term, it may also increase business to US chip firms (and by extension, Malaysia) through displacement as well as front-loading. However, if the US strategy of explicitly adding large chip-producing capacity over the medium and long term materialises, it does raise the risk of future diversion of US chip demand away from Malaysia-based output and capex (capital expenditure) and intensifies competition for non-US market share,” she adds.

In 2024, Malaysia’s exports to the US totalled RM198 billion, of which RM120 billion consisted of E&E products — making up 20% of the country’s total E&E exports. Of these RM120 billion worth of E&E exports, semiconductor products made up RM60.6 billion or half the total.

Zafrul also says changes in the US trade policy cannot be taken lightly, given the significance of the US market as there will be tangible implications whenever the White House makes policy changes.

“The E&E industry supports roughly 72,000 skilled workers across 7,200 domestic suppliers, many of which are SMEs (small and medium enterprises). SMEs cannot afford to be complacent and act merely as vendors for the MNCs without technological and technical capacity to manufacture their own products,” he says, adding that SMEs need to position themselves and complement the MNCs in Malaysia.

“Not a zero-sum game”

While it may seem to some that Malaysia has yielded too much to the US in return for a 19% tariff rate, Zafrul disagrees that the country got a raw deal.

“Whether we like it or not, the US is a very important trading partner for Malaysia. It is Malaysia’s largest export destination with an export value of RM198.65 billion in 2024 as well as the biggest source of foreign investment amounting to RM32.82 billion. I have maintained that this relationship is mutually beneficial and that trade is not a zero-sum game.”

Economists and analysts also do not see the current tariff situation as a zero-sum game. But they do not deem it mutually beneficial either. They say it would be more apt to call it a negative-sum game, where all parties will likely incur net losses.

RAM Rating Services Bhd economist Nadia Mazlan says higher tariffs damage all the parties involved — where one party faces lower export demand, which translates into lower economic activity, while the other party faces higher import prices, potentially lifting inflation and slowing consumer demand.

“For the country facing tariffs, the options are limited. Either accept the higher tariffs, retaliate and risk a trade war or try to cut a deal for lower tariffs. In Malaysia’s case, the latter is likely the best option, given that accepting the higher tariff rate of 25% would make Malaysia’s exports to the US less competitive than those from Indonesia (US tariff rate of 19%), the Philippines (19%), and Vietnam (20%),” she points out.

With the US accounting for about 13% of Malaysia’s total exports, Nadia opines that, while not ideal, dampening the blow by securing a lower tariff rate of 19% compared to 25% previously may be more beneficial to the country’s growth prospects despite the concessions made.

Institute of Strategic & International Studies Malaysia analyst Jaideep Singh, who also sees both sides losing as a result of the US’ extensive and unpredictable tariff policy, says there is little empirical or theoretical evidence that tariffs alone would achieve the Trump administration’s objective of reshoring manufacturing, particularly in sectors where the US ecosystem is underdeveloped or too costly to develop within a short time frame, such as semiconductors.

He says it would be a stretch to conclude that Malaysia ceded “too much” to US demands as sensitive sectors like cars, tobacco and alcohol remain unaffected. Instead, he says, it is important to note that the concessions are far from punishing for Malaysia given that the Malaysian market is already fairly open to begin with.

“Malaysia’s trade-weighted tariff with the US was just 1.9% (with an overall trade-weighted tariff of 3.5%) in 2023. This means that many of Malaysia’s most critical imports from the US were already duty-free even before the deal was announced,” notes Jaideep.

Zafrul had previously told a press conference that Malaysia will eliminate or reduce tariffs on 98.4% of total tariff lines. He had also said that 60% of the tariff lines, or 6,911, will be zero-rated.

Where non-tariff measures are concerned, Jaideep does not find the concessions to be particularly extensive and believes that Malaysia merely offered the low-hanging fruit.

“For instance, Malaysia simply upholds its commitment to non-discrimination in the application of the Digital Services Tax without explicitly calling for US companies to be excluded. Other concessions are in highly specific areas, such as the exemption to the mandatory contribution to the USP Fund for telecommunications,” he notes.

It should be noted that much of the US$240 billion investment commitment to the US announced by the Malaysian government during the special parliamentary session last week is not new investment cut in order to secure the tariff deal.

For instance, the Boeing purchase of US$19 billion. This has been part of the Malaysia Aviation Group’s plan to replace older Boeing 737 aircraft.

The national air carrier had announced in March that it would acquire 30 new aircraft from The Boeing Company as part of its fleet modernisation strategy where the order includes 18 Boeing 737-8 and 12 Boeing 737-10 aircraft, with the option for 30 more 737 aircraft.

Zafrul also says the US$70 billion investment in the US over a 10-year period represents “a broad and strategic outlook on long-term economic engagement between both countries”, where the investments will primarily take place in the form of market-driven decisions by private sector companies and investments by government-linked companies as well as government-linked investment companies in the US capital markets aimed at generating long-term returns for contributors.

Zafrul also says the US$70 billion investment in the US over a 10-year period represents “a broad and strategic outlook on long-term economic engagement between both countries”, where the investments will primarily take place in the form of market-driven decisions by private sector companies and investments by government-linked companies as well as government-linked investment companies in the US capital markets aimed at generating long-term returns for contributors.

It is worth noting that, in June, Petroliam Nasional Bhd, through its subsidiary Petronas LNG Ltd, entered into a liquefied natural gas (LNG) sale and purchase agreement with Commonwealth LNG, LLC for one million tonnes per annum for 20 years, from Commonwealth’s facility under development in Louisiana, the US. This is included in the US$240 billion investment commitment to the US.

Currently, Malaysia’s investments in the US are valued at US$43.5 billion, according to Miti, covering sectors such as oil and gas, automotive, retail, financial services, home furnishing, real estate, oleochemicals, information and communications technology, food manufacturing and rubber gloves, among others.

So, did Malaysia really get a raw deal or is it merely a reiteration of the eventual organic growth and future investments to be made by Malaysian companies in the US?

Malaysia has reiterated that it did not overstep “red lines”, safeguarding national interests. Economists say this is a prudent move to ensure that the country does not get shortchanged.

“This is especially so with the current unpredictability of US trade policies.

Malaysia must remain firm on its boundaries so as to set a precedent for future negotiations, if any,” says Nadia.

Jaideep takes a similar view, saying that crossing red lines would suggest that the country could be “bullied” into submission through tariff threats that contradict Malaysia’s open but firm approach to liberalisation in past free trade agreements, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

“This is why Malaysia is making a concerted effort to formalise the deal through an Agreement on Reciprocal Trade, signalling its commitment to the rules-based order,” he says.

Regional comparison

Based on newsflow, it seems that some countries in the region have given up a lot to secure a trade deal with the US.

Based on newsflow, it seems that some countries in the region have given up a lot to secure a trade deal with the US.

Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam appear to be required to liberalise their markets to a much greater extent than Malaysia.

MARC Ratings Bhd chief economist Dr Ray Choy says this could be simply a reflection of the fact that some countries have relatively high initial levels of trade protectionism, requiring the removal of multiple barriers to facilitate freer trade.

However, he opines that it is difficult to measure whether certain countries have been disproportionately disadvantaged in these negotiations, given the lack of transparency and complexity surrounding non-tariff measures.

Thus, Choy says, the quantifiable tariff rate should remain the primary reference point for evaluating the outcome of tariff negotiations.

He adds that it is well understood at this point that tariff rates play a central role in geopolitical posturing, where the key lies in the adopted narrative.

“One perspective might highlight the success of negotiations, noting that the reciprocal tariff rate has declined from 25% to 19%. Alternatively, a more cautious view would point out that tariffs, once in the single-digit, initially rose to a baseline of 10%, followed by a further increase to 19%.”

Choy adds that another prudent approach is to consider the global average tariff rate of 14% or the median of 10% as the benchmark, rather than to compare solely with Asean peers, which may be affected by small sample bias and difficulty in justifying qualitative distinctions.

“Even countries facing a ‘modest’ 10% tariff continue to adopt a cautious stance, focusing on strategic manoeuvring to make the most of ongoing negotiations,” he notes.

Choy believes a balanced approach — one that acknowledges risk, responds to challenges and continuously recalibrates trade policy — is likely the most constructive way to navigate the current phase of trade tensions.

This article first appeared in The Edge Malaysia on 18 August 2025