IN the last few months, Malaysia has seen increasing crackdowns on activists and civil society members – from iconoclastic graphic designer Fahmi Reza to, most recently, 20-year-old Sarah Irdina from youth-run collective Misi Solidariti. Others in this cohort include journalists, healthcare workers and Heidy Quah, who runs NGO Refuge for the Refugees.

This renewed zeal is ostensibly part of efforts to maintain public peace and stifle dissent as the government of the day continues to battle internal instability. However, this approach is not just poorly thought-out in cold-blooded policy terms – it is also a violation of the right to free speech and expression.

Reduces faith in public institutions

The Covid-19 pandemic and its accompanying flurry of rules and regulations have created a restive populace struggling with the burden of economic woes, strained mental health and general uncertainty. It has also seen reduced faith in public institutions, most starkly illustrated by the recent negative perceptions of Parliament and criticisms of the police for practicing “double standards” in investigating those caught flouting Covid-19 distancing rules.

For the state to now take action against individual citizens merely engenders deeper mistrust in our institutions at a time where national unity and cohesion is paramount to the fight against the virus. The perception of a draconian clampdown – coupled with mixed messaging from leaders, viz. ministers calling for police probes to be dropped or promising no action will be taken – will only result in Malaysians harbouring greater mistrust and/or confusion regarding institutions that should, at this crucial juncture, be seen as pillars of stability.

Antithetical to democratic values

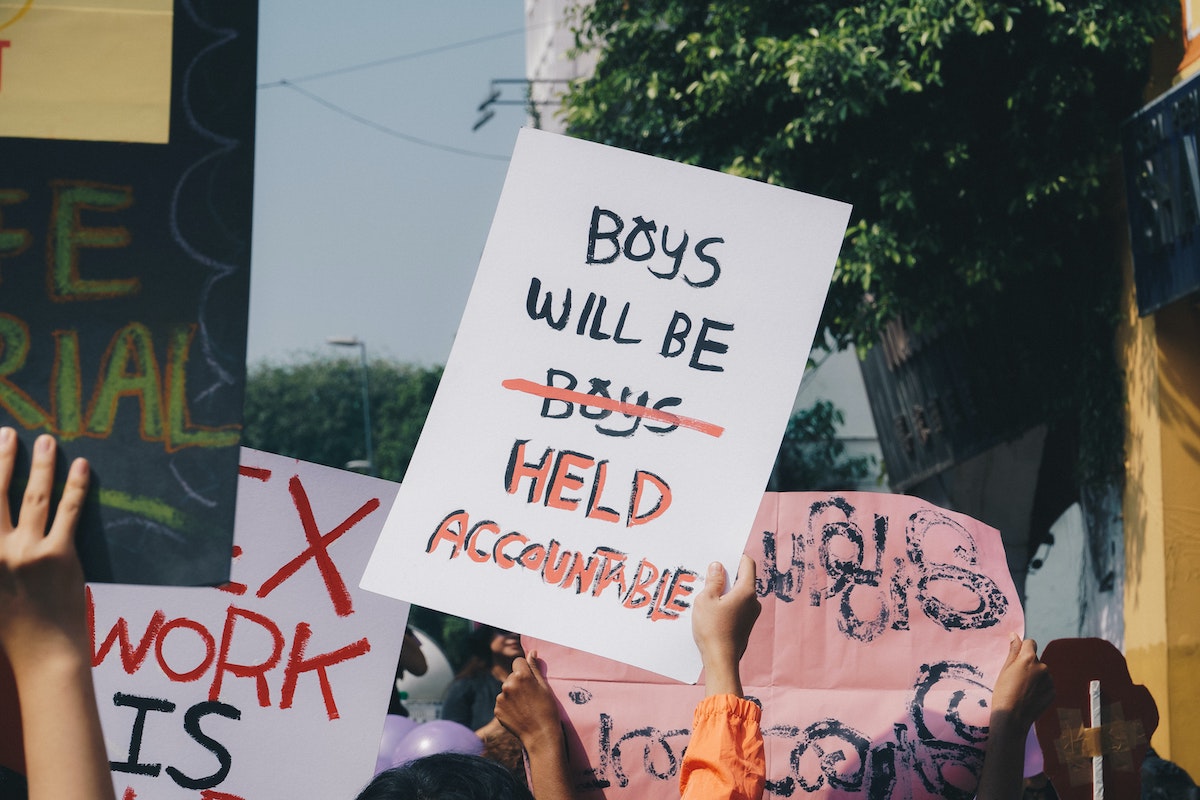

To haul up youths, artists, activists and journalists – even if just for questioning – runs contrary to the values of democracy that are the lifeblood of any progressive and successful nation. Malaysia has a celebrated and illustrious history of nonconformists pushing the envelope and by doing so bringing about changes that are, ultimately, positive. Think of Rasammah Bhupalan, BH Oon, Irene Fernandez – all struck out against the status quo and are now celebrated as nation-builders and heroes.

Dissenting opinions are vital to discourse and dogmatism is poison to new ideas even when it comes to those who criticise the government. After all, if Parliamentarians can criticise each other surely normal citizens should be able to as well?

To investigate artists, writers and activists for merely doing their jobs will eventually result in a closed society that does not value going against the grain, shutting down radical and potentially valuable new ideas.

Makes enemies out of potential allies

It is the role of NGOs and journalists to address perceived lacunae in governance and policy. This is a valuable role – whistleblowers, outlier viewpoints and watchdogs eventually strengthen processes and goals rather than the opposite. Ideally, the government should be allowing people like Sarah Irdina, Heidy Quah and the folks at youth group Undi18 to continue in their work unhampered, and potentially exchange ideas with them on how to better serve the people.

To illustrate: Heidy Quah, who was recently charged for a Facebook post made last year on the state of immigration detention centres, has fed 65,000 families in need over the last 12 months. This is no mean feat and by all accounts should be an achievement that is appreciated by a government that is struggling to ensure that people do not go hungry amidst the economic lockdowns that have resulted in median salary returning to 2016 levels.

Several lawmakers have acknowledged the helpfulness of these groups in registering people to get vaccinated, assisting undocumented migrants, and even food aid.

Given this, it is clear the government should seek coexistence, not clampdowns: governments and activists or journalists do not have to agree, but surely the goal of national stability should be a unifying one. Further, coexistence is vital in a pandemic and post-pandemic world where the duties of aiding marginalised groups cannot and will not be the exclusive arena of the executive.

Bridging the chasm

It is worth noting – although this is not a new observation – that there is a large chasm between the average activist and the government. Those who join governments and those who join NGOs often come from quite dissimilar backgrounds in terms of assumptions about the role of the executive, the fundamental nature of laws and lawmaking, and perspectives on political association.

While it would be a large ask for governments to view NGOs and journalists as partners (or vice versa – indeed, the approach must be in some ways adversarial to maintain integrity), it would be prudent for lawmakers to avoid passing up the chance to serve the people presented or represented by activists, artists, journalists and the work they do.

Given the above, it is imperative that the Malaysian government halt what are widely perceived as unfair crackdowns on freedom of speech and democratic criticism – it will only result in increased mistrust, erosion of democratic ideals, and a host of missed opportunities.

This article first appeared in Malay Mail Online on 29 July 2021.