The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has come a long way since its founding in 1967. The organisation now encompasses almost all Southeast Asian countries and is regarded as one of the most successful regional organisations of its kind. Yet will ASEAN be able to navigate these challenging times of insecurity?

If ASEAN were a country, it would be the world’s seventh largest and is projected to be take the fourth spot by 2050. Its economy has grown almost 100-fold and now boasts a combined GDP of around US$2.8 trillion. The establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015 marked a major milestone in its efforts on regional economic integration.

Its political and security achievements are no less impressive. In a region fraught with conflicts since the end of World War II, ASEAN Member States have never, despite their various disputes, had any serious armed clash amongst themselves. Many of the existing regional multilateral regional economic, strategic and security arrangements – Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), East Asia Summit (EAS) and ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting (ADMM) Plus – were either initiated by ASEAN or see ASEAN as a key component. All in all, it plays a central role in wider regional stability.

Another significant, but often underplayed achievement, is the establishment of the Socio-Cultural Community – which aims to improve the quality of life of its peoples through cooperative activities that are people-oriented as well as environmentally friendly and geared towards the promotion of sustainable development. Given ASEAN’s emphasis on the sovereignty of member states in terms of policymaking and the sensitivity on encroaching on one’s internal affairs, it is quite remarkable that there are now groups at various levels – ministers, senior officials, technical committees and non-governmental organisations – discussing and, at times, attempting to harmonise various policy matters on education, sports, women and family development, poverty eradication and healthcare.

However, while much has been achieved, most observers and stakeholders are in agreement that ASEAN is undergoing tremendous challenges. These are both externally imposed and originate from within the organisation and its member states. What makes them all the more significant, but tough, is that they are taking place amidst a broader regional environment of uncertainty – where disruptive issues run rampant and longstanding established norms, including multilateralism, are increasingly being ignored by states.

One critical external challenge with potentially severe consequences is the impact of major power competition, in particular the dynamics between the United States and China, on the cherished yet rather ambiguous “centrality” of ASEAN. This dynamic, which is increasingly competitive and possibly adversarial, has contributed to the wider geostrategic flux in the wider region. While ASEAN has kept itself relatively disentangled from such rivalry, there are signs of this beginning to unravel. Both major powers do hold significant sway over different ASEAN Member States. Indeed, both can and will either ignore ASEAN or work to sway decisions when it suits them.

Nowhere is this more visible than in how ASEAN has had to manage the South China Sea dispute, which involves several member states as littoral claimants. ASEAN communiques and joint statements on the matter have become a largely predictable and timid affair, given how some member states effectively use what amounts to a veto to block the adoption of language and statements that would lend greater urgency to the concerns posed by China in the dispute.

The trade element of the US-China dynamic, largely coloured by the infamous trade dispute or trade war between the two major powers, also bring up another troubling concern for ASEAN and its member states. Many members of ASEAN are at different levels of development and depend on trade, heavy investment or, in some cases, aid, from the two major powers and their allies. The more developed economies of ASEAN are also closely connected to the global supply chains of both major powers. While some sectors here might have benefitted from the dispute, the longer and more protracted this trade dispute gets, the worse the risks for ASEAN Member States, especially if the tit-for-tat sanctions worsen.

Despite the constant reassurances by both the United States and China that they do not desire to undermine ASEAN cohesiveness and neutrality, many observers and stakeholders in this region perceive just the opposite. In fact, some further argue that given the state of affairs between the two major powers, it is not in their interests to allow ASEAN a relatively free reign to play a bridging role in the regional security and strategic architectures.

On the internal front, despite the significant progress mentioned earlier, ASEAN continues to face challenges in terms of unequal growth, meaningful economic integration and the need for sustainable development. Many of these are longstanding – especially developmental gaps and opportunities between different member states. Access to technology, education and even banking facilities vary significantly between the more developed member states and those in the bottom rungs. Despite the various milestone goals and achievements under the AEC, there are questions whether the less developed countries of ASEAN have really benefitted as much as their better off siblings. It is not uncommon to hear the sentiment that the latter have largely ignored the former when it comes to quality economic initiatives and this has caused some resentment.

Further compounding this is the fact that ASEAN is home to young, literate and increasingly urbanised and aspirational populations. Member states are confronted with demands to help their young populations meet the challenges of a modernised world. ASEAN governments will need to work closely with the private sector and non-government organisations to adopt innovative approaches and achieve sustainable solutions.

Last, but not least, domestic developments within countries – including insecurity in the Southern Philippines – and natural disasters remain a challenge for the regional organisation and its member states. While there has been a concentrated multilateral effort to address the latter, the former remains a hot-button for many regional observers. Here, the issue of displacement in Myanmar, particularly of the ethnic Rohingya from the Rakhine state is a longstanding and prickly issue for the regional organisation. For member states like Malaysia, in particular, it is an increasingly urgent matter as there are real concerns about state-sanctioned genocide that has been taking place, as well as the large numbers of displaced Rohingya that are present in, and headed to, Malaysia.

Given such circumstances, the discussion on how ASEAN and its member states can effectively respond is a common one in conferences, presentations and articles these last few years. And at the rate things are going, it might remain that way for the foreseeable future.

One of the most recommended suggestions is for ASEAN to strengthen its Secretariat and various mechanisms and agencies in terms of personnel, funds and powers. A more effective Secretariat is crucial towards strengthening ASEAN’s internal centrality and dealing with some of the challenges mentioned above. There is a clear need for the Secretariat to step up its role in monitoring member states – in terms of deliverables and publicising relevant Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). But this is an extremely touchy matter for member states – with many fearing even an indication that the ASEAN Secretariat could become more like the European Commission, with executive powers that occasionally surpass those of national governments.

Another common narrative when it comes to prescriptive measures has been the need for more ASEAN leaders to step up to the mantle during these times of uncertainty. Some observers, especially veteran ones, pine for the days when “strong” regional leaders like Suharto, Mahathir Mohamad, Ferdinand Marcos and Lee Kuan Yew publically advocated for ASEAN and its relationships when dealing with major powers. They bemoan the decreased sense of regionalism among today’s leaders who seem more concerned with national priorities, sometimes at the expense of ASEAN.

Yet perhaps it is this overreliance on “leaders”, what more of the strongman variety, which has contributed to ASEAN’s current conundrums. Rather than leaders, the emphasis should perhaps be on leadership – which is more enduring than the former. The challenges ASEAN faces, and the organisation itself, have changed. The type of leadership it needs must morph accordingly. There needs to be a focus on institutions and instilling the proper processes and safeguards. Whether ASEAN and its member states are prepared to do this, however, is another question.

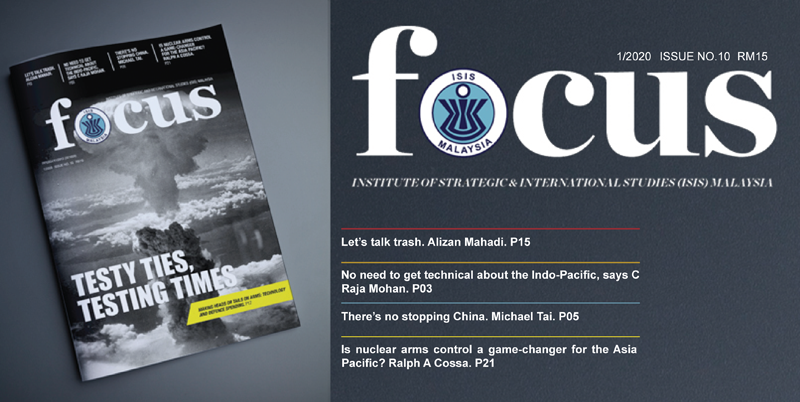

This article first appeared in the ISIS Focus 1/2020 No. 10