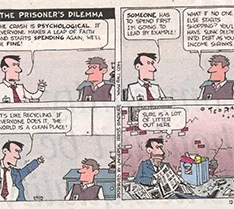

The prisoner’s dilemma is a canonical example of why rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interests to do so. We need to think about how to break out of this mentality and avert a national crisis before a much larger on befalls us.

EFFORT: It is hard enough to bring about changes at the best of times, what more when social cohesion is lacking

Things happen for a reason, and they also don’t happen for a reason. Few things happen as a result of change or luck.

One thing that doesn’t happen, at least not as much as is talked about, is economic reforms -bold, decisive and good-for-the-country changes to how the economy is run.

We all want the benefits of having a stronger economy -higher productivity, incomes and the associated status and prestige -but none of the personal costs and inconveniences that inevitably come with it. In short, we want our cake and we want to eat it, too.

We know intuitively that our country would be better off through cooperation and collective effort. Yet, it is in no individual community’s, organisation’s or individual’s interest to cooperate and make that effort and sacrifice.

We demand that things remain the way they are for us, and demand for someone else, including the government, to deliver outcomes efficiently and painlessly for us. And we are prepared to back up our reasoning with all sorts of logical and illogical thinking.

This is the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) that we learn in Political Science 101. The dilemma of wanting the greater good, but not at our personal expense, is not just the result of heated emotional outbursts but cool realist thinking.

In constricted policy space, we keep discussing and doing the same things repeatedly, waiting and hoping for outcomes change. We resort to the same sorts of budget policies, dressed up in new terms, hoping that something will give or change.

It is hard enough to bring about economic changes at the best of times, what more when a nation is in the process of losing its social cohesion. This is akin to speeding up rather than slowing down when faced with the prospect of a head-on collision.

Amidst incidences of unaccountable governance, street protests, racist diatribes and attacks on state institutions, inspired (or at least not discouraged) by political leaders, the PD grows ever larger, and with it, the ever diminishing hopes and aspirations of the nation.

The answer is not better speeches, economic policies or instruments. What we require are the socio-political conditions that tackle the PD problem and allow policies that shape a better future to be implemented.

Without doubt, divisive sectarian politics is the chief culprit. Faced with problems of performance and accountability, the tendency of those in power is to be more illiberal and restrictive, rather than liberal and conciliatory.

Rather than pursue progress and moderation, the stage, floor and room are given to reactionary extremists who seek to wield power in their narrowly construed interests, even while justifying their actions that not to do so would be “against” the nation’s interests.

Thus, the privileged and powerful can be heard to justify their position and actions, on the grounds that for them not to do so would be a “violation” of the nation’s sovereignty or the “betrayal” of public trust -at least as they interpret it.

Simultaneously, the deprived and powerless justify their vehement protests and opposition based on the acts of corruption, unaccountability, partiality and imperviousness, perpetrated (or perceived to be) by those in power.

Such a situation is rarely static. Over time, performance suffers and the number of disillusioned and disaffected tends to grow, many from the outer ranks of the elites. The latter shrinks and becomes ever more fearful at the loss of power, and ever more vindictive.

Forgotten in all of this are the economic reforms and policies that make a stronger and more resilient and vibrant economy. These become mere fodder for defence and attacks. Everything and anything appears fair game in the world of divisive ethno-religious politics.

To be fair, this country’s experiences are replicated in many others, differing only by degree. A few countries manage to overcome it, many others muddle through, while yet others go in exactly the opposite direction.

A few have managed to make relatively peaceful democratic transition to populist governments, who then proceed to repeat the failed autarkic experiments of the past and disengage with the rest of the world.

We need urgently to think long and hard about how to break out of the processes described and avert a national crisis before a much larger one befalls us. Pragmatic economic reforms are needed, whoever is in power and whatever their political persuasions happen to be.

Article by Dato’ Steven Wong which appeared in New Straits Times, 20 October 2015.